Dev Diary #43 - Events 📰

What's happening / TLDR: Developer diaries introduce details of Espiocracy - Cold War strategy game in which you play as an intelligence agency. You can catch up with the most important dev diary (The Vision) and find out more on Steam page.

---

If you search Wikipedia for the genre of Espiocracy, "grand strategy game" (GSG), you won't find an article with such title. Instead, you will be redirected to "wargames", focused on military strategy, "that include Risk". It is probably the only description of Risk as a grand strategy wargame on the entire internet. In an interesting parallel - perhaps authored by like-minded people - this article unapologetically invents proprietary takes as much as the (actual) genre itself.

GSGs are famous for their unusual gameplay with multi-layered maps, spreadsheet menus, dense tooltips, and a plenitude of popup events. The last feature is where much of history, storytelling, flavor, DLCs, and modding happens in the genre.

Initially, Espiocracy implemented events typical for GSGs. However, during two years of development, these turned out to be too detached from mechanics, negatively impacting gameplay flow, lowering replayability, and even subtly encouraging lazy takes on the history. The table has been flipped (for some time, the main build had completely no events) and after many iterations, the game arrived back at a fundamentally different approach to events.

Now, instead of random external triggers that conclude in a popup interrupting gameplay, events in Espiocracy highlight mechanical changes in the world. They do not disrupt main strategic gameplay, do not uncontrollably descend on the player, and do not feature ad hoc decisions that give arbitrary modifiers. It's no coincidence that two weeks ago we explored reports - while reports are about objective rundowns of continuous & wider situations, events focus on more immersive representation of punctuated & local changes in the world.

To achieve this, the notion of global random events has been dropped entirely. Instead, events work in three precise frameworks.

[h2]Contextual Events[/h2]

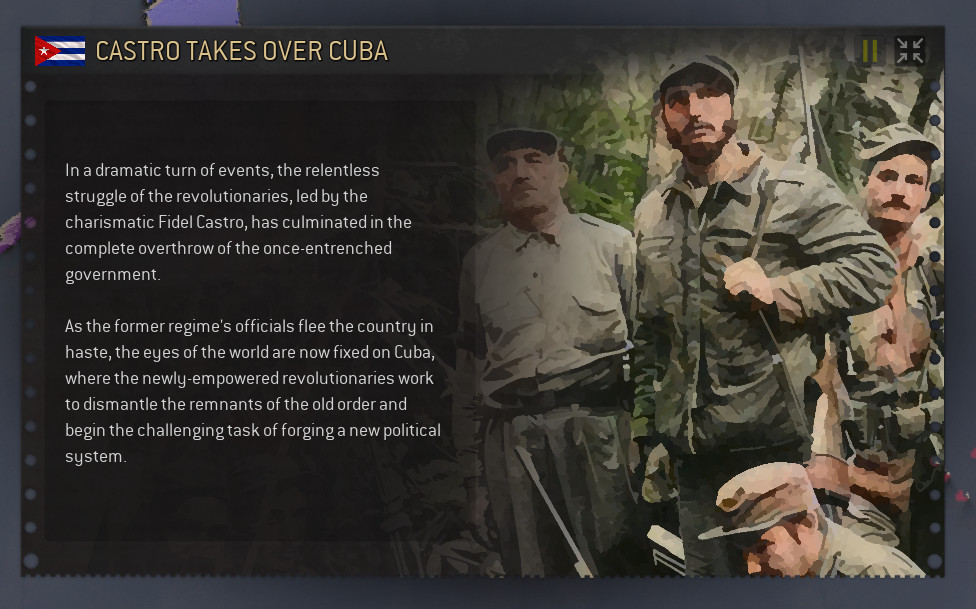

As the history unfolds around the player, contextual events communicate significant developments in the world. They are purely descriptive and celebratory, intending to slightly enrich spreadsheets and maps with (alt-)historical texts and graphics.

The very first contextual event welcomes the player on March 5th, 1946:

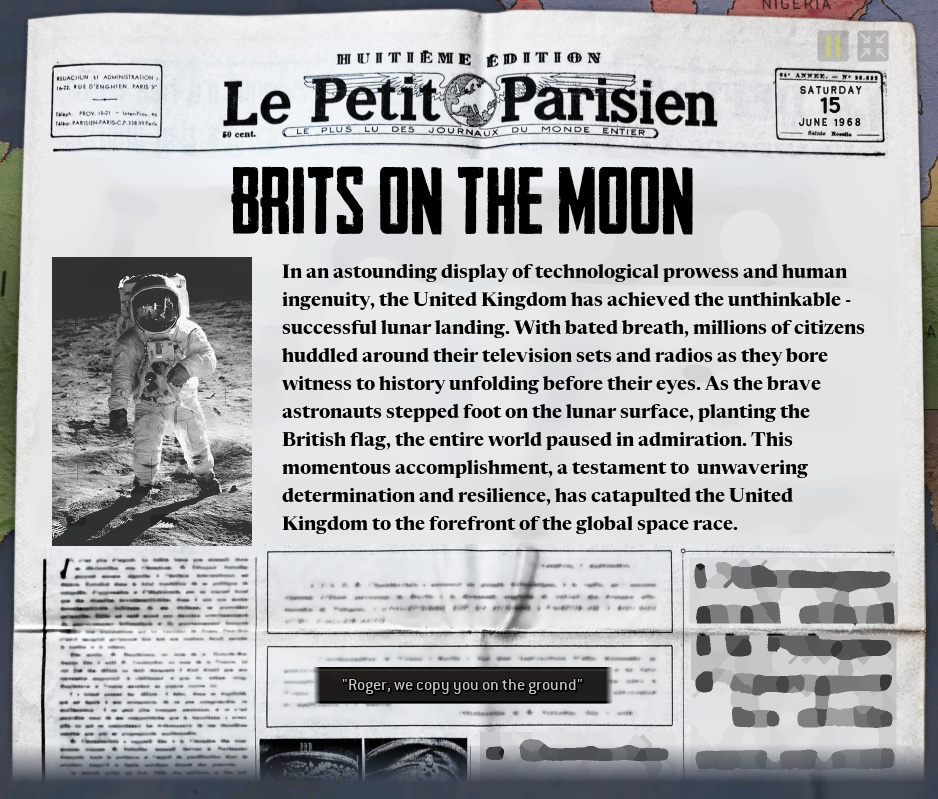

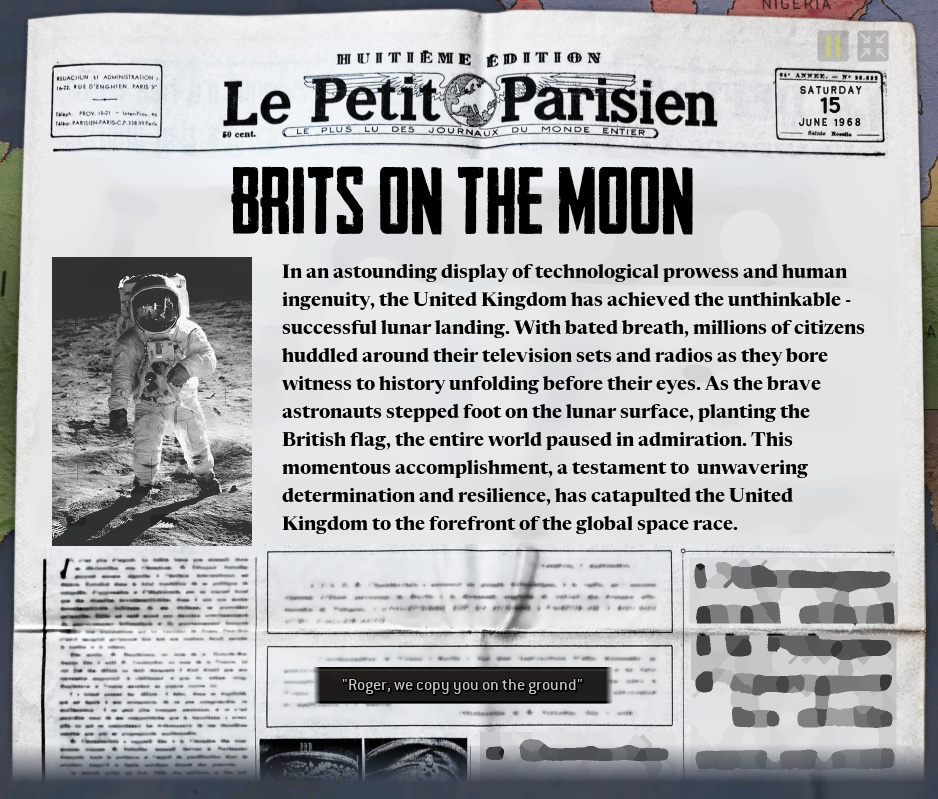

Similar newspaper template is also used for changes in the world that are critically important for the player (= usually involve player's country) such as new wars, unifications, divisions, or... pulling off landing on the Moon.

Text of contextual events is prepared in multiple versions: one universal variant with replaceable nouns/adjectives, and other variants written for historical or very probable alt-historical variants. In the case of landing on the Moon, the event has special texts for American and Soviet landings, while all the other variants (including the above screenshot) are more generic.

Changes less important than landing on the Moon but still judged as important enough to surface to the player, the game uses a teletype layout that has been previously featured in a few dev diaries. Examples of such events include the beginnings or ends of regional conflicts, paradigm shifts, deaths of important actors such as Stalin, important political changes in relevant countries, and so on.

[h2]Narrative Events[/h2]

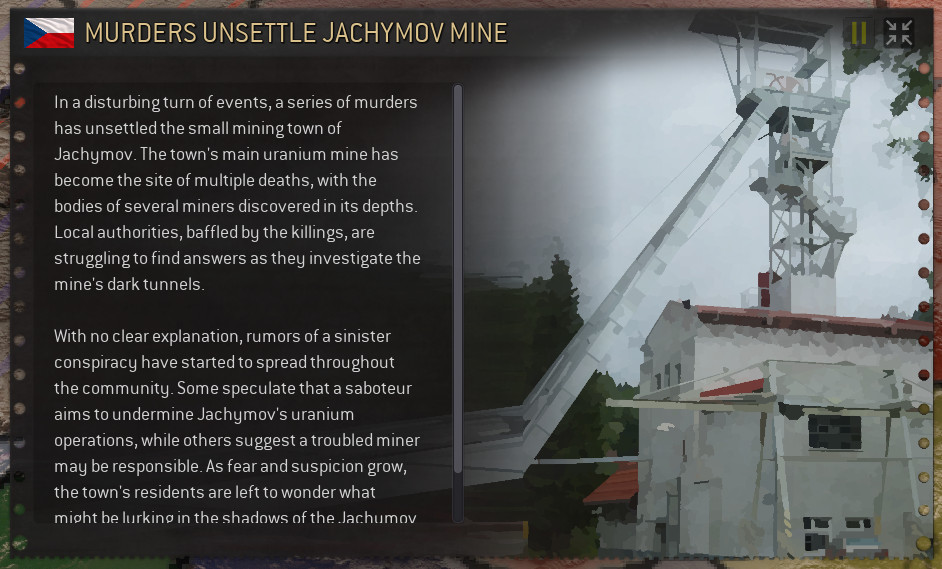

In a natural next step after reactive and mostly generic events described above, narrative events are active (they can cause small changes in the world) and precise (always tied to a specific local entity). They contribute to flavor of a particular country, an actor, or other entities (e.g. a paradigm), sitting firmly in the realm of (plausible) history, and bridging the gap between mechanics - which are never deep enough - and fascinating details that made us all fall in love with history.

In a process not far from classic GSG events, narrative events have a chance of happening at specific points defined by time and/or arising conditions. They can (but do not have to) modify their subject in a clear & limited manner: only by adding or removing traits.

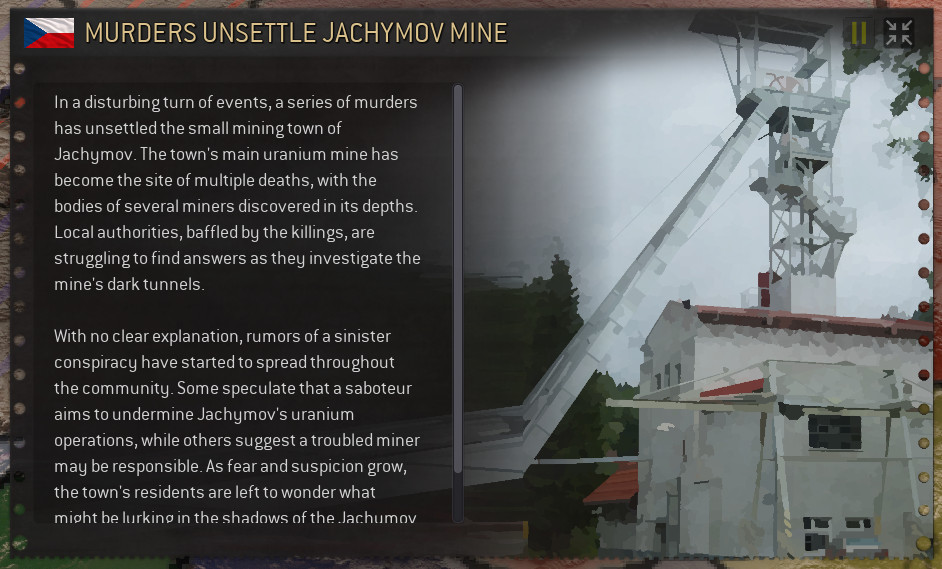

As a long-standing example of such an event, take a look at an interesting detail about uranium mines in Czechoslovakian Jachymov that made it to the game:

This event is exclusive to "Jachymov Mine" actor, can happen with a total chance of 40% (20% check in 1946, 20% check in 1947), it subtly modifies the situation by adding a "recently disrupted" trait (which may for instance influence ongoing operations around this important target) and is sourced from real events around the mine (and will be further iterated upon n times).

[h2]Random Encounters[/h2]

The next step, after working with history, leans more into the intersection of espionage, history, and the map. Unlike previous categories, random encounters directly interact with the player. They constitute meaningful discoveries, procedurally and regularly planted on the map, that can be unearthed by nearby operatives and stations of any player. In a way, these are an incentive to explore the map as passing through a particular city may be enough to pick up an interesting encounter there.

The details of planting are a bit convoluted and still in the process of working out but players can roughly expect encounters tied to regions, political systems, or local environment. Examples include discovery of WW2 documents, meeting a stranger in bar that leads to an opportunity, or even ability to pull off classic RPG-ish robbery on the road.

[h2]Final Remarks[/h2]

Currently, player attention is managed directly by a set of interaction and importance scores (eg. you'll get Jachymov events after interacting with the mine) compared to the measure of how busy is the player (eg. active x operations in parallel means fewer events). This solution will definitely evolve further to include notifications and other elements competing for player's attention and hence was not explored yet in a dev diary.

This was brief overview of general approach to events. We will definitely return to them, perhaps even individual categories, in the future.

The next dev diary will be posted on May 26th.

If you're not already wishlisting Espiocracy, consider doing it

https://store.steampowered.com/app/1670650/Espiocracy/

There is also a small community around Espiocracy:

---

"That's too coincidental to be coincidence" - Yogi Berra

---

If you search Wikipedia for the genre of Espiocracy, "grand strategy game" (GSG), you won't find an article with such title. Instead, you will be redirected to "wargames", focused on military strategy, "that include Risk". It is probably the only description of Risk as a grand strategy wargame on the entire internet. In an interesting parallel - perhaps authored by like-minded people - this article unapologetically invents proprietary takes as much as the (actual) genre itself.

GSGs are famous for their unusual gameplay with multi-layered maps, spreadsheet menus, dense tooltips, and a plenitude of popup events. The last feature is where much of history, storytelling, flavor, DLCs, and modding happens in the genre.

Initially, Espiocracy implemented events typical for GSGs. However, during two years of development, these turned out to be too detached from mechanics, negatively impacting gameplay flow, lowering replayability, and even subtly encouraging lazy takes on the history. The table has been flipped (for some time, the main build had completely no events) and after many iterations, the game arrived back at a fundamentally different approach to events.

Now, instead of random external triggers that conclude in a popup interrupting gameplay, events in Espiocracy highlight mechanical changes in the world. They do not disrupt main strategic gameplay, do not uncontrollably descend on the player, and do not feature ad hoc decisions that give arbitrary modifiers. It's no coincidence that two weeks ago we explored reports - while reports are about objective rundowns of continuous & wider situations, events focus on more immersive representation of punctuated & local changes in the world.

To achieve this, the notion of global random events has been dropped entirely. Instead, events work in three precise frameworks.

[h2]Contextual Events[/h2]

As the history unfolds around the player, contextual events communicate significant developments in the world. They are purely descriptive and celebratory, intending to slightly enrich spreadsheets and maps with (alt-)historical texts and graphics.

The very first contextual event welcomes the player on March 5th, 1946:

Similar newspaper template is also used for changes in the world that are critically important for the player (= usually involve player's country) such as new wars, unifications, divisions, or... pulling off landing on the Moon.

Text of contextual events is prepared in multiple versions: one universal variant with replaceable nouns/adjectives, and other variants written for historical or very probable alt-historical variants. In the case of landing on the Moon, the event has special texts for American and Soviet landings, while all the other variants (including the above screenshot) are more generic.

Changes less important than landing on the Moon but still judged as important enough to surface to the player, the game uses a teletype layout that has been previously featured in a few dev diaries. Examples of such events include the beginnings or ends of regional conflicts, paradigm shifts, deaths of important actors such as Stalin, important political changes in relevant countries, and so on.

[h2]Narrative Events[/h2]

In a natural next step after reactive and mostly generic events described above, narrative events are active (they can cause small changes in the world) and precise (always tied to a specific local entity). They contribute to flavor of a particular country, an actor, or other entities (e.g. a paradigm), sitting firmly in the realm of (plausible) history, and bridging the gap between mechanics - which are never deep enough - and fascinating details that made us all fall in love with history.

In a process not far from classic GSG events, narrative events have a chance of happening at specific points defined by time and/or arising conditions. They can (but do not have to) modify their subject in a clear & limited manner: only by adding or removing traits.

As a long-standing example of such an event, take a look at an interesting detail about uranium mines in Czechoslovakian Jachymov that made it to the game:

This event is exclusive to "Jachymov Mine" actor, can happen with a total chance of 40% (20% check in 1946, 20% check in 1947), it subtly modifies the situation by adding a "recently disrupted" trait (which may for instance influence ongoing operations around this important target) and is sourced from real events around the mine (and will be further iterated upon n times).

[h2]Random Encounters[/h2]

The next step, after working with history, leans more into the intersection of espionage, history, and the map. Unlike previous categories, random encounters directly interact with the player. They constitute meaningful discoveries, procedurally and regularly planted on the map, that can be unearthed by nearby operatives and stations of any player. In a way, these are an incentive to explore the map as passing through a particular city may be enough to pick up an interesting encounter there.

The details of planting are a bit convoluted and still in the process of working out but players can roughly expect encounters tied to regions, political systems, or local environment. Examples include discovery of WW2 documents, meeting a stranger in bar that leads to an opportunity, or even ability to pull off classic RPG-ish robbery on the road.

[h2]Final Remarks[/h2]

Currently, player attention is managed directly by a set of interaction and importance scores (eg. you'll get Jachymov events after interacting with the mine) compared to the measure of how busy is the player (eg. active x operations in parallel means fewer events). This solution will definitely evolve further to include notifications and other elements competing for player's attention and hence was not explored yet in a dev diary.

This was brief overview of general approach to events. We will definitely return to them, perhaps even individual categories, in the future.

The next dev diary will be posted on May 26th.

If you're not already wishlisting Espiocracy, consider doing it

https://store.steampowered.com/app/1670650/Espiocracy/

There is also a small community around Espiocracy:

---

"That's too coincidental to be coincidence" - Yogi Berra